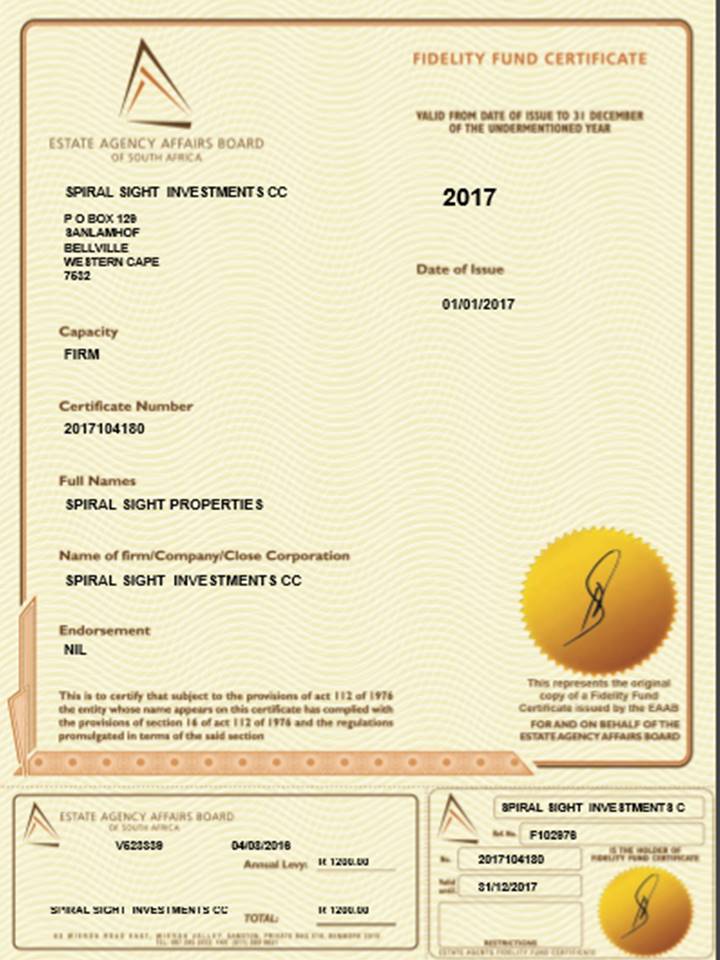

It is important to only deal with agents that is qualified estate agents. Every year an estate agent must renew his/her FFC in order to do business and must have a valid Fidelity Fund Certificate issued by the Estate Agency Affairs Board for that specific year. Even if the agents is the course of the transaction, it does not give him/her the right to earn that commission. The reason for FFC is to show the client they are competent to do the work, they are qualified, they will understand their contracts and environment, they will understand the complexities of all property transactions and to effectively guide both the buyer and the seller through the processes of selling fixed assets, they are legally registered with the Estate Agency Affairs Board (EAAB) to do business, they have done all their courses and exams, don’t have criminal record related to finances, is able to conduct a property transaction and is an upright citizen in good standing within the community, to ensure that buyers or sellers are not going to be ripped off by unethical and unprofessional agents.

Furthermore, no Attorney is allowed to pay out commission to any agent that does not have a FFC. So, don’t pay money/commission if that agent doesn’t have a FFC. Unfortunately some agent still get away with this illegal act and is it in the Public interest as well as the agent who do work legally to get rid of agents that is not allowed to do business in the property trade.

A resent reportable court case underlines this where agents, without valid FFC doing business and sellers refused to pay commission. The agents lost their case, even when they were the cause of the transaction.

THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL OF SOUTH AFRICA JUDGMENT Reportable Case No: 39/2016 In the matter between: BRODSKY TRADING 224CC APPELLANT and CRONIMET CHROME MINING SA (PTY) LTD FIRST RESPONDENT CRONIMET CHROME SA (PTY) LTD SECOND RESPONDENT CRONIMET CHROME PROPERTIES SA (PTY) LTD THIRD RESPONDENT

Neutral citation: Brodsky Trading 224CC v Cronimet Chrome Mining SA (39/2016) [2016] ZASCA 175 (25 November 2016) Coram: Cachalia, Petse, Swain, Mathopo and Mocumie JJA Heard: 7 November 2016 Delivered: 25 November 2016 Summary: Estate Agency Affairs Act 112 of 1976 – estate agent company converted to close corporation in terms of s 27 of the Close Corporations Act 69 of 1984 – Estate Agency Affairs Board not advised of conversion – fidelity fund certificate issued to non-existent company – certificate invalid – close corporation precluded from recovering commission. ORDER On appeal from: Gauteng Division of the High Court, Pretoria (Tolmay J sitting as court of first instance). The appeal is dismissed with costs, including the costs of two counsel.

JUDGMENT Swain JA (Cachalia, Petse, Mathopo and Mocumie JJA concurring): [1] The appellant, Brodsky Trading 224CC, instituted action for the recovery of estate agent’s commission against the first respondent, Cronimet Chrome Mining SA (Pty) Ltd as fourth defendant, the second respondent Cronimet Chrome SA (Pty) Ltd as eighth defendant, the third respondent Cronimet Chrome Properties (Pty) Ltd as ninth defendant (collectively referred to as the respondents) together with six other defendants in the Gauteng Division, Pretoria (Tolmay J).[1] [2] At the initial hearing before the court a quo two issues were separated for determination in terms of Uniform rule 33(4). The first issue was whether the appellant had complied with s 26 of the Estate Agency Affairs Act 112 of 1976 (the Act) and the second was whether it had complied with s 34A(1) and (2) of the Act. Section 26 prohibits any person from performing any act as an estate agent, unless a valid fidelity fund certificate (certificate) has been issued to him or her. In terms of s 34A read with the definition of ‘estate agent’ in s 1, no estate agent is entitled to any remuneration for any work, unless at the time the work was performed a valid certificate had been issued to the estate agent concerned. [3] The court a quo issued a declaratory order to the effect that the appellant had ‘substantially complied’ with these provisions, and then granted leave to the respondents to appeal against this finding. This court, however, decided that the issue was not appealable and the matter was struck from the roll. It would be a fruitless exercise if the court a quo ultimately decided that the Act and hence the need for a valid certificate did not apply to the transaction, or to a large part of it on the basis that it did not fall within the definition of ‘business undertaking’ in s 1 of the Act. In the absence of a determination of this issue by the court a quo, the order was not definitive of the rights of the parties and would not dispose of a substantial part of the relief claimed.[2] [4] At the resumed hearing the court a quo, after hearing evidence on the merits, decided that what was sold was indeed a ‘business undertaking’. In the light of its previous conclusion that the appellant had substantially complied with the requirements of the Act regarding the validity of the certificates, it decided that the appellant was not precluded from recovering commission. However, on the merits of the claim, it found that the appellant had failed to prove that the first respondent had granted a mandate to it to sell the shares, property and permits and dismissed the action. Leave to appeal to this court was thereafter granted by the court a quo. [5] The appellant makes the following submissions with regard to its entitlement, to claim commission: (a) It supports the court a quo’s finding that it substantially complied with the requirements of the Act regarding its possession of a valid certificate, but (b) Submits that the court a quo erred in finding that the sale of the shares held by the first, second and third defendants in the first respondent, to the second respondent, constituted the sale of a ‘business undertaking’ as contemplated in s 1(a)(i) of the Act. [6] The respondents, however, contend that the court a quo erred in concluding that the appellant had substantially complied with the requirements of the Act. This remains an issue in the appeal as it was not dealt with by this court at the previous hearing. It is also submitted that the court a quo correctly concluded that what was sold, was indeed a ‘business undertaking’ in terms of the Act. [7] The evidence of relevance to these issues is as follows. A certificate was issued on 6 May 2005 to a company Brodsky Trading 224 (Pty) Ltd, which was valid until 31 December 2005. According to Mr Brian Maree, a director, the company was converted in terms of s 27 of the Close Corporations Act 69 of 1984 (the CC Act) to the appellant, Brodsky Trading 224CC, a close corporation, as from 20 March 2006. No valid certificate was issued to the company or its directors, or to the close corporation or its members, for any period during 2006. On 6 May 2007 a certificate was issued to Brodsky Trading 224 (Pty) Ltd (the non-existent company), but not to the appellant, Brodsky Trading 224CC. On the same date a certificate was issued to Mr Maree in his former capacity as a director of Brodsky Trading 224 (Pty) Ltd and similarly not in his capacity as a member of the appellant, Brodsky Trading 224CC. [8] Mr Maree believed he did not receive a valid certificate for 2006 because, according to him, there were years when he did not receive certificates from the Estate Agency Affairs Board (the Board). It was possible, he speculated, that 2006 was one of those years and that if a valid certificate had been issued, it would have been among the documents he had discovered. He initially stated that he could not recollect whether he had informed the Board of the change in the nature of his business from a company to a close corporation. However, when cross-examined he conceded that it could be accepted that he did not tell the Board of the conversion. He also conceded that from the beginning of 2007 until 6 May 2007, there was no valid certificate in existence for the appellant. In addition, from that date until the end of 2007, the certificate was in respect of a company that no longer existed. He also accepted that from 6 May 2007 to the end of the year, the certificate was issued to him in his capacity as a director of this non-existent company. [9] According to the appellant’s amended particulars of claim, the seller’s mandate (including an entitlement to 10 per cent commission) was granted to the appellant and accepted by Mr Maree and Mr Hennie Human on behalf of the appellant, on 15 March 2007. In evidence Mr Maree stated that the mandate was in fact granted on 12 March 2007. The appellant alleged that pursuant to this mandate it commenced marketing the seller’s interests to potential purchasers. It found the sixth defendant, Mr Niemöller, as a potential purchaser, and introduced him to the sellers. Mr Maree stated that the commission was earned on 14 May 2007, when the introduction took place. [10] It is clear that neither the appellant nor its director, Mr Maree, were in possession of a valid certificate when the mandate was allegedly granted to and accepted by it on 15 March 2007. The certificate that was issued two months later, on 6 May 2007, eight days before 15 May 2007 (when it is claimed the commission was earned) was, however, not issued to the close corporation, but to the non-existent company. In addition, no valid certificate was issued to Mr Maree in his capacity as a member of the close corporation; it was issued to him in his capacity as a former director of the non-existent company. [11] It is apparent that the conclusion of the court a quo that the appellant had substantially complied with ss 26 and 34A of the Act, was based primarily on the provisions of s 27(5) of the CC Act. This section provides for the vesting of the assets, rights, liabilities and obligations of the company in the corporation and s 27(5)(b) provides that ‘. . . any other thing done by or in respect of the company shall be deemed to have been done by or in respect of the corporation’. Section 38(5)(d) provides that ‘the juristic person which prior to the conversion of a company into a corporation existed as a company, shall notwithstanding the conversion continue to exist as a juristic person but in the form of a corporation’. [12] It is, however, vital to recognise that although the juristic person that existed before the conversion, in the form of a company, continues to exist in the form of a close corporation, the company ceased to exist as at the date of conversion. Section 29B of the Companies Act 61 of 1973 provides that: ‘When a company is converted into a close corporation in terms of the Close Corporations Act, 1984, the Registrar shall, simultaneously with the registration of the founding statement of the close corporation by the Registrar of Close Corporations in terms of the said Act, cancel the registration of the memorandum and articles of association of the company concerned.’ [13] For a right to be transferred from the company to the close corporation, it must have been held by the company at the time of conversion. Likewise ‘any other thing done by or in respect of the company’ would have to be done at a time when the company was in existence for it to be deemed to have been done in respect of the corporation. On 20 March 2006, being the date of conversion, the company, however, was not in possession of a valid certificate that could be transferred to the corporation. In addition, nothing had been done by, or in respect of the company before its conversion, with regard to an application for a certificate in terms of s 16 of the Act, which could be transferred to the appellant. [14] The court a quo accordingly erred in concluding that the non-existent company possessed any rights in and to a valid certificate that could be transferred to the appellant. The court a quo’s decision was based in part upon this erroneous conclusion, but it also reasoned that: ‘. . . the fidelity fund certificates issued in the name of the company and Mr Maree as director will provide for the protection of the public’s interest as envisaged by the Act. Seeing that the object of the Act is to protect the public from unscrupulous estate agents, the object of the Act has been fulfilled.’ [15] The general object of the Act was described by this court in Rogut v Rogut 1982 (3) SA 928 (A) at 939C in the following terms: ‘The general object of the Act was to protect the public against some persons by requiring all estate agents, as defined, to take out a fidelity fund guarantee (which is not granted automatically); and to pay the levies and contributions; and by requiring all estate agents to keep necessary accounting records and to cause them to be audited by an auditor, and by obliging every estate agent to open and keep a separate trust account with a bank and forthwith to deposit therein the moneys held or received by him on account of any person.’ [16] The objectives of the Act with regard to the issue and validity of certificates are encapsulated in several of its provisions, namely ss 1, 16, 26 and 34A which, in their relevant parts, provide as follows: ‘Section 1 “estate agent” – (a) means any person who for the acquisition of gain on his own account or in partnership, in any manner holds himself out as a person who, or directly or indirectly advertises that he, on the instructions of or on behalf of any other person – (i) sells or purchases or publicly exhibits for sale immovable property or any business undertaking or negotiates in connection therewith or canvasses or undertakes or offers to canvas a seller or purchaser therefor; or . . . (b) for purposes of section 3(2)(a), includes any director of a company or a member who is competent and entitled to take part in the running of the business and the management, or a manager who is an officer, of a close corporation which is an estate agent as defined in paragraph (a); (c) for purposes of sections 7, 8, 9, 12, 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 26, 27, 30, 33 and 34B, includes – (i) any director of a company, or a member referred to in paragraph (b), of a close corporation which is an estate agent as defined in paragraph (a); and (ii) any person who is employed by an estate agent as defined in paragraph (a) and performs on his behalf any act referred to in subparagraph (i) or (ii) of the said paragraph. 16. Applications for and issue of fidelity fund certificates and registration certificates. (1) Every estate agent or prospective estate agent, excluding an estate agent referred to in paragraph (cA) of the definition of “estate agent” in section 1, shall, within the prescribed period and in the prescribed manner, apply to the board for a fidelity fund certificate, and such application shall be accompanied by the levies referred to in section 9(1)(a) and the contribution referred to in section 15. (2) . . . (3) Subject to sections 28(1), 28(5) and 30(6), if the board upon receipt of any application referred to in subsection (1) or (2) and the levies and contribution referred to in those subsections, is satisfied that the applicant concerned is not disqualified in terms of section 27 from being issued with a fidelity fund certificate, the board shall in the prescribed form issue to the applicant concerned a fidelity fund certificate or a registration certificate, as the case may be, which shall be valid until 31 December of the year to which such application relates. (4) No fidelity fund certificate or registration certificate shall be issued unless and until the provisions of this Act are complied with, and any fidelity fund certificate and registration certificate issued in contravention of the provisions of this Act shall be invalid and shall be returned to the board at its request. (5) . . . 26. Prohibition of rendering of services as estate agent in certain circumstances. – No person shall perform any act as an estate agent unless a valid fidelity fund certificate has been issued to him or her and to every person employed by him or her as an estate agent and, if such person is – (a) a company, to every director of that company; or (b) a close corporation , to every member referred to in paragraph (b) of the definition of “estate agent” of the corporation. 34A. Estate agent not entitled to remuneration in certain circumstances. – (1) No estate agent shall be entitled to any remuneration or other payment in respect of or arising from the performance of any act referred to in subparagraph (i), (ii), (iii) or (iv) of paragraph (a) of the definition of “estate agent”, unless at the time of the performance of the act a valid fidelity fund certificate has been issued – (a) to such estate agent; and (b) if such estate agent is a company, to every director of such company or, if such estate agent is a close corporation, to every member referred to in paragraph (b) of the definition of “estate agent” of such corporation. (2) No person referred to in paragraph (c)(ii) of the definition of “estate agent”, and no estate agent who employs such person, shall be entitled to any remuneration or other payment in respect of or arising from the performance by such person of any act referred to in that paragraph, unless at the time of the performance of the act a valid fidelity fund certificate has been issued to such person.’ [17] A company or a close corporation may accordingly fall within the definition of an ‘estate agent’ in terms of s 1(a) read with ss 1(b) and (c). In addition, a clear distinction is drawn in ss 26 and 34A between companies and close corporations that are estate agents and the requirement that directors of companies and members of close corporations, be in possession of valid certificates. [18] As regards the requirement in s 16(1) that every estate agent must within the prescribed period and in the prescribed manner apply to the Board for a valid certificate, Mr Maree stated that the Board sent out renewal notices for the following year to estate agents in October of each year. Indeed, Regulation 4 of the regulations published in terms of s 33 of the Act[3] provides as follows: ‘4. (1) Every estate agent to whom a fidelity fund certificate or a registration certificate has been issued in respect of a specific calendar year shall, unless he has ceased or will cease before the end of that year to operate as an estate agent and has advised the [B]oard of such fact in the prescribed manner, by not later than 31 October of that year, apply to the [B]oard for the issue to him of a fidelity fund certificate or registration certificate, as the case may be, in respect of the immediately succeeding calendar year.’ [19] The certificates issued on 6 May 2007 contain the following endorsement: ‘This is to certify that subject to the provisions of Act 112 of 1976 the person whose name appears on this certificate has complied with the provisions of s 16 of Act 112 of 1976 and the regulations promulgated in terms of the said section.’ (Emphasis added.) [20] Section 16(4) provides that no certificate shall be issued unless and until the provisions of the Act are complied with. As from the date of conversion, being 20 March 2006, the company no longer existed. When application was made for a renewal of the certificates in 2007 it must have been made in the name of the company, because Mr Maree conceded that he had not told the Board of the conversion. The application was accordingly made by a non-existent company, Brodsky Trading 224 (Pty) Ltd, which no longer qualified as an ‘estate agent’ in terms of the Act. The certificate therefore purported to certify compliance with the requirements of the Act by a non-existent company, in the guise of an ‘estate agent’. [21] Section 16(4) of the Act provides that any certificate issued in contravention of the Act shall be invalid. The issue of the certificate to the non-existent company was accordingly invalid. In addition, the issue of a certificate to Mr Maree in his capacity as a director of the non-existent company, and not in his capacity as a member of the appellant, did not comply with s 16 of the Act and was also invalid. In terms of s 26 of the Act, every director of a company and every member of a close corporation, is required to have a valid certificate. In their absence the company or close corporation concerned is not entitled to receive any remuneration in terms of s 34A of the Act. On this additional ground the appellant is precluded from recovering any remuneration. [22] This is not simply an issue of nomenclature, or a misdescription in the name of the certificate holder, but one of substance. The objectives of the Act are not fulfilled by the issue of invalid certificates by the Board as they play a central role in ensuring that estate agents comply with its provisions. There was accordingly no basis for the court a quo to conclude that the appellant had substantially complied with its requirements. [23] I turn to the issue of whether the sale of the shares held by the first, second and third defendants in the first respondent, to the second respondent, constituted the sale of a ‘business undertaking’ as contemplated in s 1(a)(i) of the Act. If not, the appellant would only be precluded from receiving commission in respect of the sale of the immovable property, and not in respect of the sale of the shares and permits. [24] In Moodley v Estate Agents Board 1982 (4) SA 257 (D) at 261G the meaning of a ‘business undertaking’ in the Act was described as follows: ‘But it is quite clear that the reference to “business undertaking” in the definition section must mean the entire undertaking of a business and not any transaction which a businessman may enter into or any individual transaction in the course of the business.’ [25] The court a quo found that the appellant in its particulars of claim alleged that the seller’s mandate was to ‘find a purchaser for their interests in the whole of the mining operation conducted by them’ inclusive of their shareholding in the first respondent, as well as the immovable property described as Vlakpoort no 38, and the crushing permit. It was also alleged that the defendants were ‘desirous of acquiring mining rights in a chrome mining operation, which they intended pursuing and exploiting jointly’. The court a quo concluded that the evidence was that ‘essentially the whole of the business of the sellers were sold’. [26] Mrs Nel, one of the sellers, stated that up until 6 February 2008, income was earned from the sale of minerals. If they had not sold the shares in the company, Platinum Mile Investments 594 (Pty) Ltd, to the second respondent, they would have continued to mine and sell chrome. She agreed that it was a business with active bank accounts and auditors and that profits were made from the recovery of chrome. Together with the other shareholders in the company, they were the owners of a chrome mine business that they decided to sell. The manner in which the business was sold was to sell the shares in the company to the second respondent. One of the objects of the sale agreement was to sell the business and the purchase price was not only for the immovable property, but also included the business. She agreed with the proposition that the appellant claimed commission not only in respect of the sale of the land, but also for the sale of the business. [27] At the resumed hearing before the court a quo, Mrs Nel agreed that the initial global price of R270 million was calculated on the basis that what was sold and bought, was a business undertaking. Mr Gunther Weiss, the attorney representing the German company Cronimet Mining GmbH (Cronimet), which acquired a majority shareholding in the second respondent, stated that the shares in the first respondent were purchased in order to acquire the company that owned the mining permits. The permits were the core assets of the whole mining business. What was acquired were the shares in the first respondent, the immovable property and the crushing permit owned by the company Night Fire Investments 110 (Pty) Ltd. These three assets formed the mining business undertaking that the purchasers wished to acquire. Although the agreement included a share deal, it was a share deal with the object of acquiring a business. [28] The issue is placed beyond doubt by several provisions in the sale agreement. Paragraph G of the Recitals records that the purchasers are interested in completing the proposed transaction ‘in order to jointly establish a new, independent chrome mining and refining beneficiation site’. Clause 2.2 provides that the sale of the shares includes ‘the right to receive profits for the current and all future financial years of the company (being Platinum Mile Investments 594 (Pty) Ltd) and the right to receive any profits of the company which have not yet been distributed’. Under the heading ‘interim period’ it is recorded that the sellers and or the company, shall ensure during the period between the signing date and the closing date, that ‘all necessary steps are taken to protect the assets and business prospects of the company and to preserve and retain the mining permits and the goodwill of the business’. These clauses are consistent with the subject of the sale being a ‘business undertaking’. [29] The court a quo was therefore correct to conclude that the sale of the shares fell within the ambit of a business undertaking as contemplated in s 1(a)(i) of the Act. In the result the appellant is not entitled to any remuneration in terms of s 34A of the Act with regard to the performance of the mandate, allegedly granted to it by the first respondent to sell the shares, immovable property and permits. This conclusion renders it unnecessary to determine whether the court a quo correctly concluded that the appellant had failed to prove the mandate upon which it relied. I shall, however, briefly deal with this aspect. [30] The cause of action originally pleaded by the appellant was of a mandate granted by the sellers to the appellant to find a purchaser with an obligation on the part of the sellers to pay commission of ten per cent upon the sale price on the conclusion of a valid sale. This cause of action was confirmed under oath by Mr Maree representing the appellant, in a subsequent application for summary judgment. It was alleged that a contract was concluded on 14 May 2007 at the meeting where Mr Niemöller and nine other persons (mostly German businessmen) representing the purchasers met with Mr Maree and Mr Herman Viljoen, representing the appellant and Mr and Mrs Nel, representing the sellers. It was alleged that the purchasers, represented by Mr Niemöller, confirmed that the appellant had been the effective cause of the introduction, had earned its commission and was entitled to payment. The purchasers would thereafter deal directly with the sellers and the purchasers agreed to pay, or procure payment of the commission directly to the appellant in the event of a sale of the sellers’ interests to the purchasers (or any of them). It was also alleged that the sellers’ mandate was orally amended in that instead of the appellant’s commission being payable by the sellers, it would be payable directly by the purchasers. [31] On this pleaded cause of action the appellant relied upon an agreement concluded with the purchasers, represented by Mr Niemöller. After the defendants pleaded that this agreement constituted an unenforceable pre-incorporation contract vis-a-vis the second respondent, the appellant amended its particulars of claim to include a number of alternative causes of action that are set out below. The respondents submit that when regard is had to the original cause of action, based upon an agreement to pay commission on 14 May 2007, which was confirmed under oath, the alternative causes of action were based upon expediency and not on the true facts. The respondents submit that this conclusion is supported by the absence of any meaningful evidence, to support the causes of action. [32] The following questions arise regarding the various causes of action relied upon by the appellant: (a) Whether Niemöller was authorised to represent the purchasers at the meeting on 14 May 2007 and agreed to the payment of commission to the appellant? (b) If Niemöller possessed such authority, whether the agreement to pay commission constituted an unenforceable pre-incorporation contract vis-a-vis the second respondent? (c) Whether the joint venture between Niemcor Africa (Pty) Ltd (Niemcor) and Cronimet had been formed before the meeting on 14 May 2007 with the result that Mr Niemöller represented the joint venture at this meeting, which was accordingly bound by Mr Niemöller’s acceptance of the liability to pay commission to the appellant? (d) If the joint venture was bound to pay commission to the appellant whether it was able to avoid this obligation by adopting a company structure in the form of the second respondent? If not, whether the second respondent is bound by the joint venture’s contractual obligations including the obligation to pay commission to the appellant? (e) Whether Niemcor and Cronimet as members of the joint venture ratified the act of Mr Niemöller in agreeing to pay commission to the appellant? (f) Whether the joint venture passed the benefit of the purchase agreement to the second respondent which assumed the obligation to pay commission to the appellant? (g) Whether the joint venture conferred a benefit upon the second respondent by way of a stipulatio alteri in the form of the purchase of the mining venture that included the obligation to pay commission to the appellant, which was accepted by the second respondent? (h) Whether the second respondent is estopped from denying the liability for payment of the appellant’s commission, because of representations by the joint venture partners? (i) And finally whether the second respondent is estopped from denying that Mr Herman Viljoen had authority to represent the second respondent? [33] It is quite clear on the evidence that Mr Niemöller was not authorised to represent Cronimet at the meeting on 14 May 2007. Ms Novak’s evidence was that neither she nor her husband, Mr Pariser, attended the meeting as representatives of Cronimet, but were there to gather information about the chrome mining operation and to assess what was offered. This is consistent with the function of her company being to look for chrome mining opportunities worldwide, on behalf of clients. Her evidence that Cronimet did not know she was at the meeting and no representatives of Cronimet were present, is also consistent with this function of her company. That she would object to Mr Niemöller saying that Cronimet would buy the mine at this initial meeting, is supported by the lengthy negotiations that followed, before the successful sale was concluded. This evidence also refutes the submission made by the appellant, that because Ms Novak and Mr Pariser met with Mr Niemöller and Mr Herman Viljoen before the meeting, it can be inferred that a joint venture between Mr Niemöller’s company, Niemcor, and Cronimet was informally agreed in principle. The only evidence led in this regard by the appellant was Mr Maree’s that Mr Niemöller had said that he represented ‘die Duitsers’. This evidence also refutes the appellant’s alternative submission that Mr Niemöller, Ms Novak and Mr Pariser had informally agreed in principle at this stage to a joint venture between themselves. There is accordingly no basis for a finding that Mr Niemöller represented a joint venture at this meeting, or that it was bound by Mr Niemöller’s acceptance of the liability to pay commission. [34] The conclusion that Mr Niemöller was not authorised to represent Cronimet and that he could not have been at the meeting as a representative of a joint venture as none had been formed, renders it unnecessary to consider whether any agreement to pay commission by Mr Niemöller, was an unenforceable pre-incorporation contract, vis-a-vis the second respondent. In addition, whether any joint venture was able to avoid an obligation to pay commission by adopting a company structure, does not have to be considered. The most probable conclusion on the evidence is that Mr Niemöller was only representing his own company, Niemcor, at the meeting. [35] Whether Niemcor and Cronimet as members of the subsequently formed joint venture ratified the act of Mr Niemöller in agreeing to pay commission, is determined by the evidence of Mr Weiss and Mr Heil that the first time Cronimet heard of the appellant’s claim to commission, was when the summons was received. In addition, Mr Weiss, Cronimet’s attorney stated that Mr Bayle, Niemcor’s attorney, at no stage raised with him any undertakings made by Mr Niemöller with regard to the payment of estate agent’s commission. Mr Weiss, Mr Heil and Ms Novak all stated that no mention was made during an earlier meeting in Dubai of any obligation to pay commission to the appellant. It is therefore clear that Cronimet as the other member of the joint venture never ratified the conduct of Mr Niemöller in agreeing to pay commission, because it was not aware of this undertaking. Therefore the joint venture could not have ratified the conduct of Mr Niemöller. [36] Whether any joint venture passed the benefit of the purchase agreement, including the obligation to pay commission to the second respondent, is also determined by the fact that no joint venture had been formed at the time of the meeting on 14 May 2007. That Cronimet was never aware of any undertaking made by Mr Niemöller to pay commission to the appellant, means that the joint venture between Cronimet and Niemcor, could never have conferred any benefit upon the second respondent, by way of a stipulatio alteri. [37] I turn to the issue of whether the second respondent is estopped from denying the liability to pay commission, because of representations made by the joint venture partners. In other words, whether the second respondent is estopped from denying representations made by Mr Niemöller as to the liability to pay commission to the appellant. It is trite that an estoppel can only operate against the person making the representation save where it is made through a duly authorised agent,[4] or where that person negligently enabled another person, acting fraudulently, to make the representation to the person raising the estoppel.[5] In this case, the representations were allegedly made by Mr Niemöller on behalf of the joint venture and not of the second respondent. This would not justify an estoppel against the second respondent. In addition, there is no evidence to show that the second respondent negligently allowed Mr Niemöller or the joint venture, acting fraudulently to make such representations to the appellant. There is accordingly no basis for this submission. [38] The remaining issue is whether the second respondent is estopped from denying that Mr Herman Viljoen had the authority to represent the second respondent. It is alleged by the appellant that Mr Niemöller and Mr Herman Viljoen represented to and misled the appellant, that they were authorised to represent the second respondent and to bind the second respondent with regard to the second respondent’s liability to pay commission to the appellant. It is clear, however, that a valid estoppel requires a representation by the principal regarding the agent’s authority. A representation of authority by the agent is insufficient.[6] [39] In the result the appeal fails and the following order is made: The appeal is dismissed with costs including the costs of two counsel.

K G B Swain

Judge of Appeal

Appearances: For the Appellant: S J Bekker SC (with W J Bezuidenhout) Instructed by: Van Wyk Fouchee Inc c/o Louw Attorneys, Pretoria Symington& De Kok, Bloemfontein

For the Respondent: A Kemack SC (with E Eksteen)

Instructed by:

Werksmans Attorneys

c/o Friedland Hart Solomon & Nicolson, Pretoria

Honey Attorneys, Bloemfontein